A Fine Line: Curator's Notes, by Penny Siopis

A Fine Line | Colin Richards | Curated by Penny Siopis | Origins Centre | 16 August-2 September

Curator’s Notes

A Fine Line is an exhibition of works by Colin Richards (1954-2012) which meditates on the relationship between Richards’s early career as a medical illustrator and his later practice as a fine artist of exceptional repute. Placed in dialogue with one another, these interweaving bodies of work suggest something of Richards’s remarkable talent in both fields of line-making. Richards himself gave careful thought to the effects on his evolving practice of these two careers. Reflecting on the connection he came to perceive between the demands of scientific drawing and the formalist art training of his day, Richards writes that in both cases ‘to be “professional” was to be distant, dispassionate; in a sense, not fully human, but technically in control’. A Fine Line attests to Richards’s lifelong endeavor to redefine professional life as a rigorous intellectual and practical commitment both to technical excellence and to the humanistic values for which he became so well-known and admired.

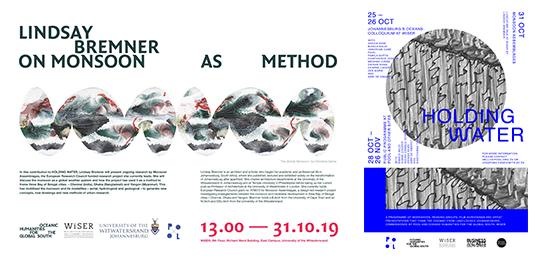

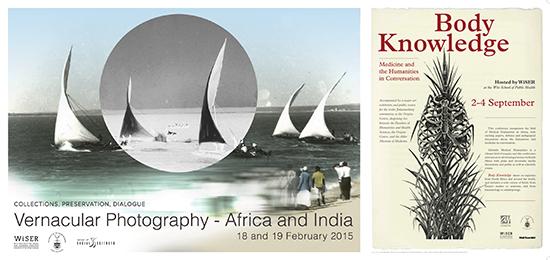

Presented by the Origins Centre, A Fine Line forms part of a wider foray at the University of the Witwatersrand into the field of Medical Humanities, and is particularly associated with an international conference entitled Body Knowledge: Medicine and the Humanities in Conversation, hosted by WiSER. Guided by the rubric of this fertile dialogue across disciplines, I have chosen to focus on Richards’s abiding creative and critical concern with illustration as a paradigm that is capable of bringing together distinct bodies of knowledge and spheres of scholarship. Richards saw illustration as ‘a hinge between the visual and the linguistic, which could turn in many ways’. It is this idea of a hinge – which connects and which can open, close and pivot – that informs my curatorial eye in this exhibition.

For me, the hinge is both a line that connects different dimensions of Richards’s oeuvre as well as a flexible mechanism which enables us to place these different elements in creative relationship with one another. The fineness of the line emphasized by the title of the exhibition invokes both the subtlety of Richards’s line of thinking across disciplines as well as the exquisitely delicate lines of his drawing. For Richards, the line was a capacious idea as much as it was the foundation of his creative practice: the line includes and separates; it is inside and outside of its delineations; it connects and transforms; it creates illusions even as it reveals ‘truths’.

The line was also, in Richards’s practice, a way of working through an idea or an experience: this is evident in his meticulous and labour intensive process of shaping form through an intense build-up of minute lines in ink or watercolour or cut-out strips of found text. The exhibition illustrates in its cabinet display of Richards’s notebooks as well as in its hung images how central the idea of the line as a line/lines of text was to Richards’s concept of the accretion of meaning.

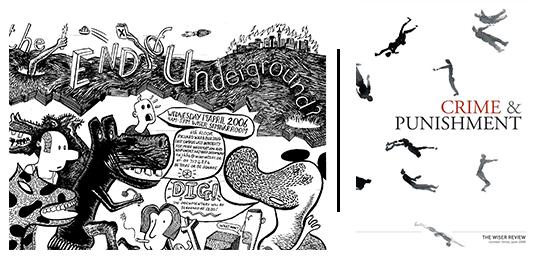

Elements of this exhibition illustrate Richards’s therapeutic practice of line-making, including when he worked with other processes of image making such as the photograph. A complex example of this is his Biko series which was made for the exhibition Inquiries into Truth and Reconciliation (1996), and which references a critical moment for the artist when, as a medical illustrator in 1977, he encountered postmortem photographs of Steve Biko. Richards was profoundly affected by his realization that the forensic photographs he had been asked to label for a legal inquest were of Biko’s body. This shocking realization provoked a deep sense in the artist of his complicity with the apartheid abuses which had martyred Biko. A careful reading of the exhibition reveals that these fraught feelings arising out of his engagement with his political milieu were made more complex still by his early loss of his brother and his father; together, these painful experiences impelled Richards to ask questions in his art about the nature of power and powerlessness; about fatherhood, childhood and masculinity. In several pieces, he works on these questions through lines of found text: from sources as diverse as lines from Beckett to fragments of recorded speech such as legal testimony. In the Biko series, these cut-out and layered lines of text combine with photographs of a prior art work Richards had created: fabric (to signify the shroud as well as the veil) that Richards had made by hand and upon which he had imprinted mediated versions of the Biko photographs that had so disturbed him when he had realized their signification. The labour- and time-intensive processes which all of the works in A Fine Line encode suggest something of how Richards inhabited artistic practice: as an absorption in making materials, layering images, drawing, painting, mixing media, establishing reference points, and carefully building repetition and newness – all of which occupied his body and mind in a process of working through time, emotion, idea and expression. These were his meticulously observed and cross-hatching lines of practice.

Like the idea of the line, and itself composed of delicately filmy lines, the veil in the Biko series gestures towards ideas of the real and of illusion and copy; it also reflects on the overlapping activities of covering and of revealing. The veil refers to ‘the Veronica’, a cloth allegedly baring the imprint of Christ’s face following its use by Veronica to wipe away the suffering man’s blood, sweat and tears as he labored towards Calvary. As an image which appeared magically, in the absence of human agency other than the impulse of compassion, ‘the Veronica’ might be imagined as the first photograph. Richards’s repeated exploration of such images echoes his childhood fascination with medical illustrations. He writes: ‘I recall all through boyhood never quite believing human beings actually made these drawings – sitting down somewhere, with their hands, bodies, minds and actually doing what seemed to be magic’. Read together, Richards’s veil images (from Endgame onwards) and his earlier medical drawings reflect on the truth claims of forensic photography as much as they affirm the mysterious capacity of the line to show us something of our intimate and human connectedness.

In placing strictly scientific drawings alongside freely imaginative works, I have wanted to emphasize the centrality to Richards’s career of drawing by hand: of the embodied agency of the artist and of the traces of the drawing body in the completed work. This notion of handmade and embodied work is given further substance in the exhibition by a display of Richards’s notebooks which invite the viewer to contemplate the artist’s creative process mediated between idea and artwork by the inscribing and interpreting work of the hand.

A Fine Line reflects in other ways, too, on the relationship between body, agency and image-making: when Richards was a medical illustrator scientific research necessitated by-hand drawing in order that certain aspects of anatomy and specimen, inaccessible to the camera, could be rendered. Nowadays, of course, digital technology has paradigmatically altered the scene. In addition to contemplating the subtle relationships between Richards’s scientific and artistic careers, this exhibition reflects poignantly on a practice and philosophy of illustration which hinged on the intimacy between line and hand.